Rohingyatographer: The photography magazine from the world’s largest refugee camp

Rohingyatographer: The photography magazine from the world’s largest refugee camp

In the world’s largest refugee camp, a group of young Rohingya residents has put together Rohingyatographer, the first photography magazine created by refugees.

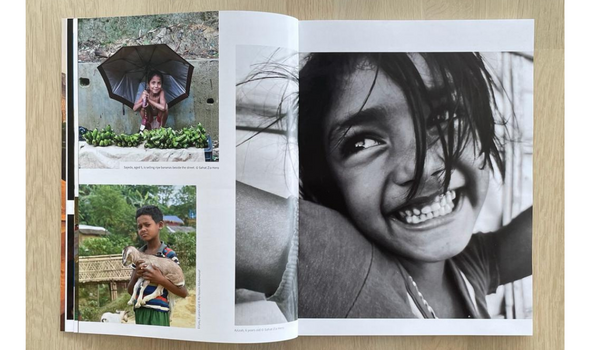

In glossy, high-quality photos, from youngest to oldest, the inhabitants of Kutupalong, in Cox’s Bazar, southern Bangladesh, are portrayed in the first issue, published earlier this year.

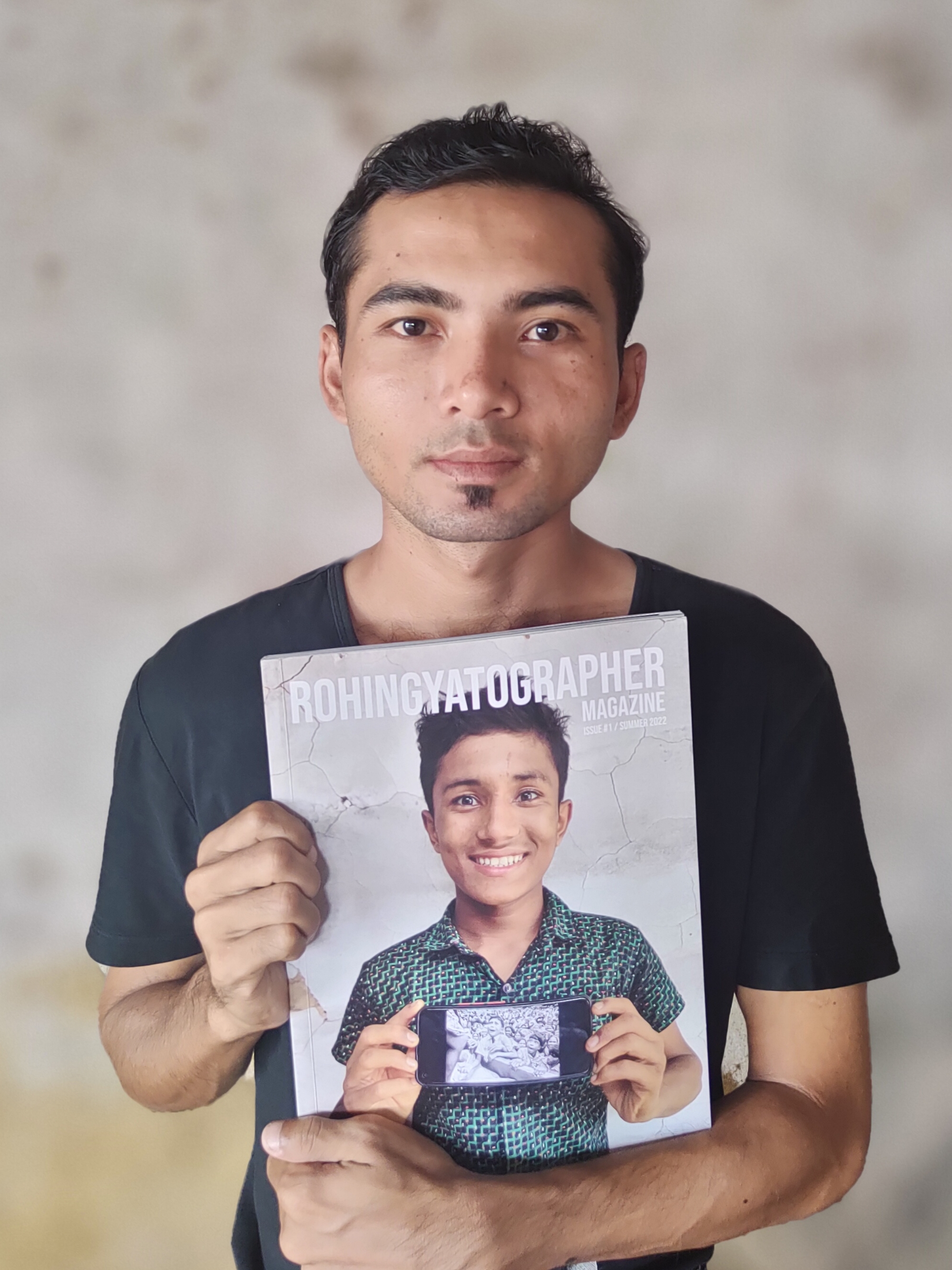

Sahat Zia Hero, the magazine’s founder, editor and one of the photographers, says the team created the magazine as a tool to reach people around the world and to campaign for their people’s rights.

“We want people to see us as human beings, just like everyone else, and we want to share our hopes and dreams, our sadness and our grief,” he explains.

About one million Rohingya refugees live in Kutupalong, hundreds of thousands of whom arrived in 2017, fleeing the genocide in Myanmar’s Rakhine state by the Burmese military.

Sahat is one of them: after experiencing years of persecution and discrimination, he and his family were forced to leave their home and move to the camp in August 2017. “My native village is very close to the border with Bangladesh. I can still see it from the camp now.”

Above: Sahat Zia Hero holds the first issue of Rohingyatographer. (Credits: Ro Yassin Abdumonaf)

Sahat has been passionate about photography since buying a smartphone in 2012. Years later, when he started working for the Danish Refugee Council in Cox’s Bazar, he used his phone’s camera to highlight the problems faced by his fellow refugees - damaged roads or shelters, broken pipes, floods - and to advocate for improvements in their precarious situation. He also targeted a wider audience by posting his pictures on social media.

In 2021, Sahat’s photos were exhibited at the Oxford Human Rights Festival, and he was selected as one of the winners of Oxfam’s Rohingya Arts Campaign.

The idea of Rohingyatographer was born after he met David Palazón, a Spanish photographer and humanitarian working as a curator at the Rohingya Cultural Memory Centre. David is the magazine’s designer, curator and mentor, having helped the team bring the magazine to life.

The magazine has received international media coverage and praise. It will come out twice a year, with the next issue planned to be published this December.

Photography is popular among young Rohingya refugees: most in the magazine’s team are in their twenties or younger.

“We use photography to advocate for our rights and try to make a difference for the Rohingya refugee community,” explains Sahat. “Photography is our superpower!”

Shahida Win, another of the photographers, agrees: “Photos speak more than words,” she says.

Shahida is a women’s rights activist and a poet; one of her poems, ‘We are Rohingya’, is featured in the magazine. She hopes her photos will reach a wide audience: “I believe our advocacy through photography, poetry and art can be the bridge to pass the messages, voices and expressions of my community to the people abroad.”

Shahida’s work has already been recognised: in 2020 she was chosen by UNHCR as a youth leader, and travelled to the UN Office in Geneva to speak on behalf of the Rohingya community.

Being a woman photographer is rare among Rohingyas, and Shahida says she feels motivated to continue her work to inspire others like her.

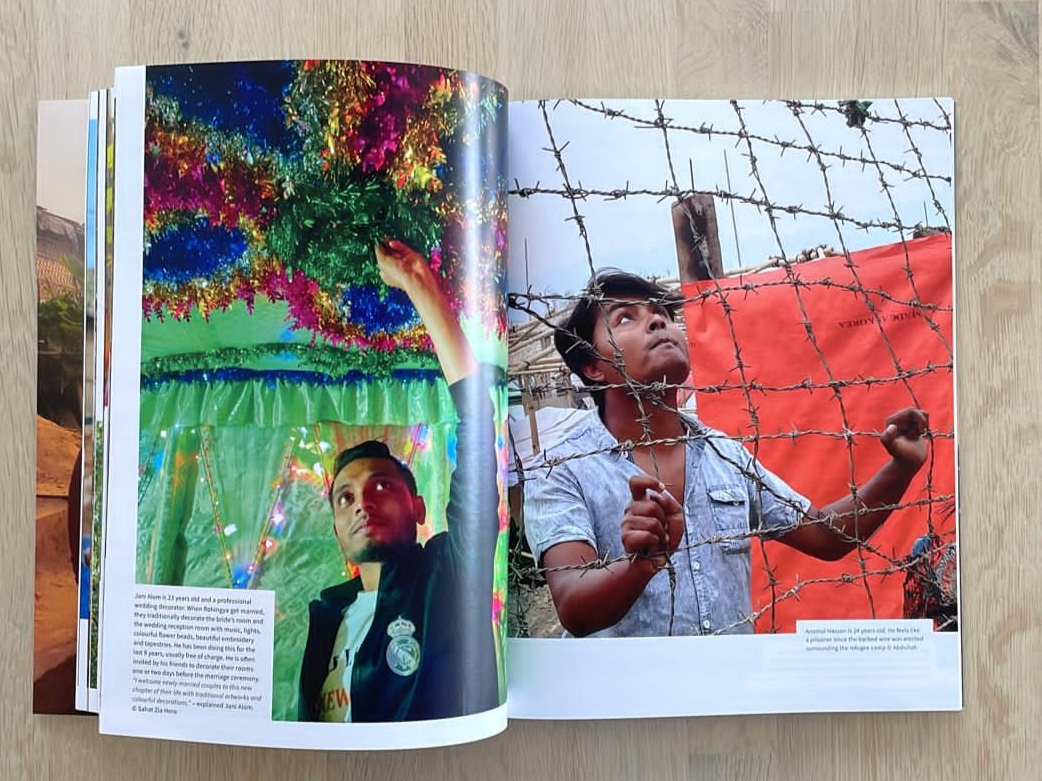

The magazine’s photos display the faces, daily lives, happiness, joy, sadness and pain experienced by the refugees. Captions explain their stories: some are heart-warming, some are heart-breaking.

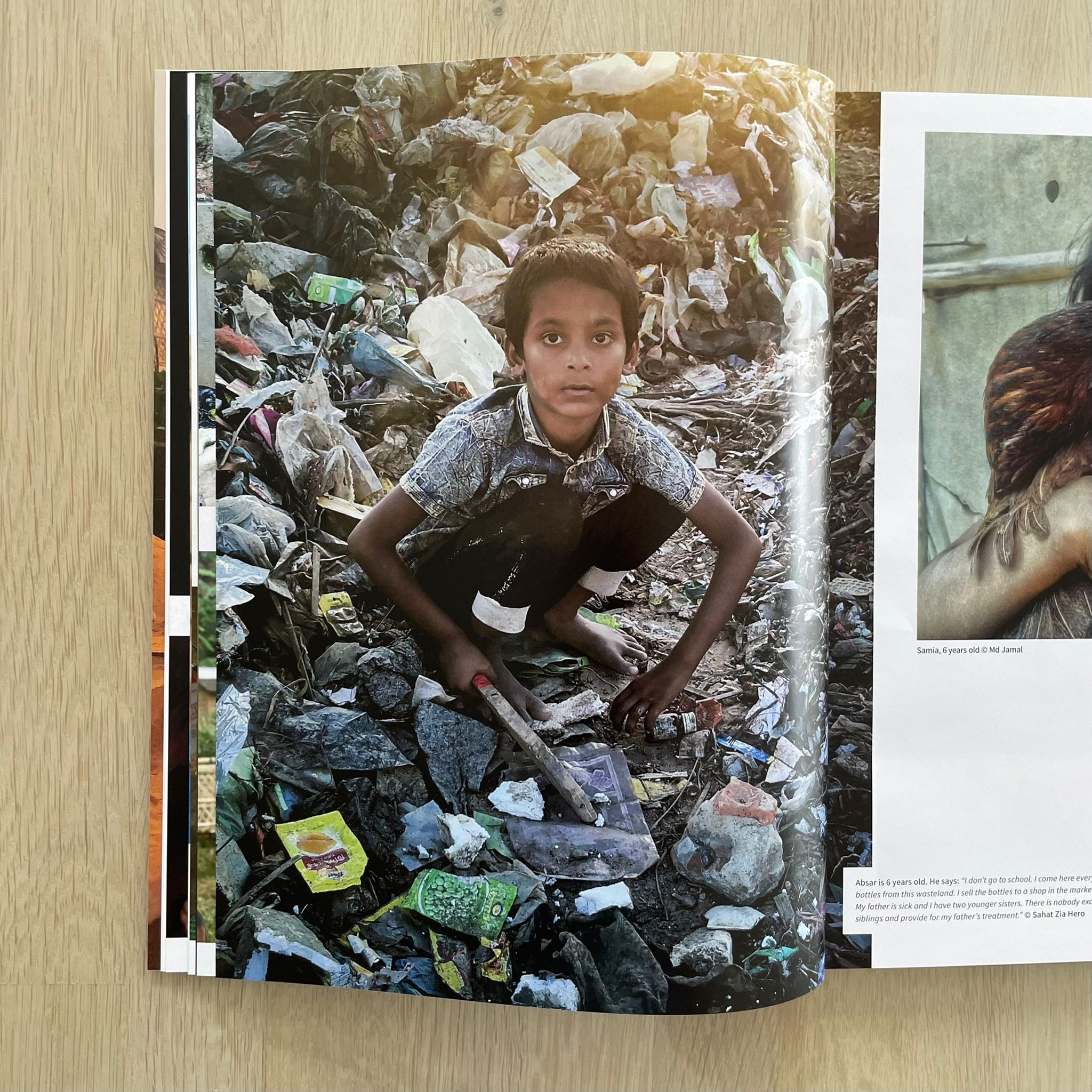

Children laugh and play in the first pages: three are photographed with masks on “to keep their identity secret because they are playing superheroes.” Elsewhere, a six-year-old is shown collecting plastic bottles in a wasteland to support his family.

Above: a refugee child is photographed looking for plastic bottles in a wasteland. (Photo by Sahat Zia Hero. The photo of the magazine was taken by David Palazón)

In March last year a fire ravaged parts of Cox’s Bazar, leaving 15 dead, 400 missing and 45,000 people displaced.

Fires in refugee camps can be far more destructive than elsewhere: barbed wire fences prevent people from escaping; packed neighbourhoods let fire spread faster and make it difficult for emergency services to reach it; the lack of infrastructure, such as water pipes, make it impossible to douse fires quickly.

Sahat’s family escaped the blaze, but the house and all his belongings were destroyed.

“I returned to find nothing but ashes where my home used to be. Nothing. My laptop and pen drives were gone. It was the second time I lost everything since I fled my home in Myanmar back in 2017,” he has said.

Despite losing everything, he managed to take a photo of his neighbour Zaudha. In the picture, featured in Rohingyatographer, she is crouching and looking at the remains of her home, amidst thick smoke and pockets of dying fire.

“I didn’t have enough words to express my sadness to her … The smoke was all that was left of our homes,” Sahat writes in the caption.

The hardships of being a refugee are what pushes the photographers in their work and advocacy.

“Photography helps us to make the people understand our hopes, challenges, happiness and the grief without writing even a single word,” says Shahida. “If we ourselves tell our stories, the world will know the reality through our eyes … So Rohingya will not be forgotten.”

Above: Life in the refugee camp. (Photos by Sahat Zia Hero and Abdullah Khin Maung Thein. The photo of the magazine was taken by David Palazón)

“Day and night, all the time, I have this feeling that I was denied the right to show my personal identity. It was taken away from my basic human rights,” Shahida explains. Rohingyatographer is the refugees’ way of fighting the erasure of their identity.

Like many forced out of their own homes, they hope to return to their homeland. Says Shahida: “My dream is to go back to Myanmar as soon as possible and rebuild a better future.”

To find out more about Rohingyatographer, click here.

Cover photo credits: David Palazón