Thinking outside the ethnic box

Thinking outside the ethnic box

.jpg)

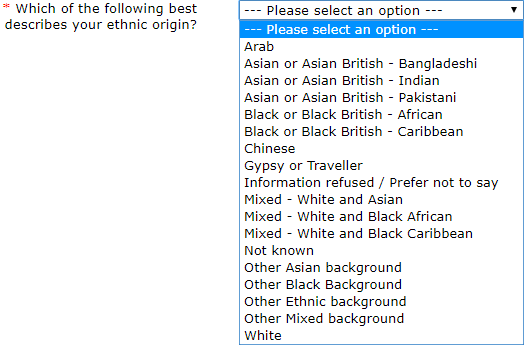

‘What is your ethnic group? Tick one box to best describe your ethnic group or background.’

That is the question that millions of UK residents face daily – when trying to complete job or higher education applications, nationwide censuses and other government-related paperwork.

According to the Office for National Statistics, ethnicity-related questions were developed with the aim of enabling organisations to monitor equal opportunities and anti-discrimination policies, and to allocate government resources more effectively in order to assist minority groups. The question first appeared on the census in 1991.

But instead of bringing clarity, these questions only generate confusion about the meaning of ethnicity and national identity in today’s United Kingdom, and remind millions of people – myself included – of their own ‘otherness’.

Since moving to Scotland two years ago, every time I encounter an ethnicity-related question, I am left dumbfounded. I feel as if none of the options available reflect my own ethnicity, for I am not just from one place – I have Argentinian and Polish passports, but these are only two pieces of a bigger puzzle.

My roots stretch far and wide – from the Middle East, to Russia and Eastern Europe, to Latin America – and my ancestors’ journeys have weaved a vibrant patchwork that I carry with me every day. I am my great-grandparents’ Jewish religion, I am my grandmother’s Polish nationality, I am my parents’ mother tongue of Argentine Spanish.

And I am the stories and hardships of the ancestors I never got to meet, the ones who prayed at the Wailing Wall, the ones who survived harsh winters in a little house on the shtetl, the ones who sailed across the ocean to begin a new life in warmer lands.

But there is no ‘It’s complicated, let me explain’ box that I can tick when I see that ethnicity question. To me, all that question does – whether it’s on a census or a job application – is to muddle the concept of ethnicity (is it to do with language? culture? nationality?) and bundle all those of mixed backgrounds into a mass of nondescript ‘Others’.

‘My identities are not, and should not be, invisible’

I first came across an ethnicity-related question when applying for Master’s degrees at British universities. Along with my grade transcript, letters of recommendation, and a personal statement, I was asked for my ethnicity, in a set of questions that mirrored the ethnicity questions presented in the UK’s 2011 nationwide census.

I remember being extremely confused by what exactly ‘ethnicity’ meant. The options available ranged from skin colour – ‘White’ or ‘Black’ – to nationality – ‘Irish’ or ‘Pakistani’ – to continents or geographic regions – ‘African’, ‘Caribbean’. It even included ‘G*psy’, a word considered by many Irish Travellers and Romani peoples as a slur.

Nevertheless, I wanted to answer the question correctly, and tried to find an option that felt suitable. I was born in Argentina, which makes me ethnically Latin American, correct? That seemed fairly easy. Except that, while ‘Asian’ and ‘African’ were provided as options, ‘South American’ or ‘Latin American’ were not.

I tried to think of another answer. Since my skin colour is white, I could be considered ethnically white, correct? Well, upon closer inspection of the first section, ‘White’, I realized that it did not refer to actual skin colour, but to nationalities and cultural groups - for the possible options were either ‘British’, ‘Irish’, ‘G*psy’ or ‘Irish Traveller’, or ‘Other’.

I was not sure whether Argentina or Poland can be considered ‘White’ nations; the very thought of a ‘white nationality’ sounds alarming and, quite frankly, ridiculous, for a diversity of skin colours can be found in Argentina, Poland, and the UK. Indeed, equating skin colour with nationality seems like a harmful way of classifying ethnicity, so I decided to find another option.

Street art in cities across the UK often takes cultural or ethnic diversity as its theme. (Darren Tennant/Flickr)

I landed on the section titled ‘Mixed/multiple ethnic backgrounds’, thinking that perhaps this would be more suitable. But my hopes were futile. I am certain that I am not ‘White and Black Caribbean’, or ‘White and Black African’, or ‘White and Asian’. White and Latin American, maybe? But writing this felt silly, as many Latin Americans are of white skin colour, including myself.

The last section: ‘E – Other ethnic group’. I glanced at the two options provided in this section. The first, ‘Arab’, confused me, given that Arab is a language as well as a cultural group; in my own case, although a Spanish person and I speak the same language, I believe we have vastly different identities.

The second, ‘Other – Write in’, puts me back where I started. I am confronted once again with being the eternal ‘Other’. But I refuse to be another number in a faceless mass of undefinable individuals. My identities are not, and should not be, invisible.

At last, I tick ‘Any other ethnic group’, and write in: ‘Argentinian, Polish, Jewish, in no particular order’.

‘I like to think of ethnicity as a little box that you carry with yourself’

My experience is not unusual. “I never know how to answer the ethnicity question,” say friends of mine who came to the UK to work or study, or who were born in the UK but have parents or grandparents from elsewhere.

In the 21st century, and particularly in a country as diverse as the UK, defining ethnicity in the form of skin colour or nationality seems awfully near-sighted. Because ethnicity is not an ascribed and stable identity; it is a social construction and therefore subjective.

Additionally, by using the concepts of ethnicity, race, and nationality interchangeably, the question generates a fragmentation in British identity, by differentiating between the concepts of British ethnicity and British nationality.

When, for example, a fourth-generation British citizen whose great-grandparents are Iraqi, possesses British nationality but is not ‘ethnically’ British, it leaves them vulnerable to not being considered ‘truly’ British – and opens the door to ostracization and racial discrimination.

Michelle likes to think of her ethnicity as a box of keepsakes. (Linda/Flickr)

In Argentina, we have a saying ‘no aclares que oscurece’, literally ‘do not illuminate because it will obscure’, meaning that the more someone tries to clarify a certain concept or situation, the more confusing it becomes.When I moved to Britain, it was precisely because of the UK’s diversity and tolerance compared to Argentina; I saw a dynamic and vibrant country, where the diversity of its people created fascinating art, ground-breaking research and incredible music.

The ethnicity-related questions in the UK’s census and other official documents fall foul of that. By seeking to refine and explain a concept that is socially constructed, subjective, and dependent on individuals’ choices, the question muddles the meanings of ethnicity and fragments the concept of British identity.

Measures should be undertaken to more accurately define what ‘ethnicity’ means in a manner that truly reflects the UK’s diversity and the hybrid nature of ethnicity. Until then, ethnicity-related questions should not be mandatory; for ethnicity should not be defined and ascribed by others.

I like to think of ethnicity as a little box that you carry with yourself, full of keepsakes from your ancestors, as well as souvenirs from the places you discover and the people you surround yourself with.

Along with my Jewish, Polish and Argentinian keepsakes, I have already placed some Scottish knickknacks, for this is the country I have embraced as my home. Your box is yours, and yours only; it is up to you what mementos you decide to keep and to whom you decide to share them with.

TOP IMAGE: Street art by Liliwenn / Bom-K in London, December 2012 (duncan c/Flickr)