Amnesia in history

Amnesia in history

Migrants to England are all too aware of a loss of identity and an absence of recognition for their efforts and contributions. One of the burdens of a migrant’s life is the difficulty of making it predictable. As Migrant Voice has observed, migrants are ignored in nearly 90% of debates about migration.

Seeking to rectify our ignorance of the 1.5 million African porters who were among the two million Africans who served in the British, French and German military during the First World War, the South African artist William Kentridge has created, with his collaborators, a theatrical work entitled The Head & the Load about amnesia in history.

The first shots of the war were fired in 1914, not on the Western Front but in Togoland, a German colony in Africa. In this extraordinary processional/cabaret performance, Kentridge sets about rectifying our lack of knowledge about – and commemorating – the thousands of expendable African porters/carriers who transported arms and equipment across Africa for the European armies.

The Head & the Load was commissioned to run in the Turbine Hall of the Tate Modern from July 11 to 15, 2018, by 14-18-NOW, the First World War centenary arts programme. Kentridge collaborated with the South African composer Philip Miller, with whom he has worked since 1994, and with the composer Thuthuka Sibisi and the dancer/choreographer Gregory Maqoma. The original music of Miller and Sibisi was combined with African songs and with elements of such modernist European composers as Maurice Ravel, Paul Hindemith and Arnold Schoenberg, who introduced a different, atonal sound into the classical Romantic tradition.

At a press conference on Saturday, July 15, Kentridge explained that the starting point for The Head & the Load had been the processional frieze of Roman history, Triumphs and Laments, which he created in 2016 along 500 feet of the banks of the Tiber River. His view was that “everyone’s triumph is someone else’s disaster.” The formal inspiration behind The Head & the Load had to do with space and music, with “ignorance” as the third element. “It was about amnesia,” Kendrick has said.

The spatial dynamics of the performance in Rome was also brought together with a psychological subject, characterised by the Georg Büchner play Woyzeck, about how a soldier is driven mad by the pressures of the military establishment. Kentridge saw this play as “a premonition of the First World War”, and spoke of how he wanted to “smash two things together” – Büchner’s play and the processional staging of Roman history. He said he was “looking for idiosyncratic moments” in the theatre rather than a play filled with facts and statistics.

The Africans’ expectations of serving in the war were that “they would be given more rights.” But instead of being given their own countries they were presented with “greatcoats and bicycles.” The war, which had initially been “a parade of all people”, of people and costumes, steadily “became more monochrome.” Africans were even excluded from the victory parades after the war. For Kentridge, “There was a deliberate shutting down of that history” as the war went on. “European poets have drowned out African voices.” The war remains “an open wound in Africa” because “the process of remembering has been excluded.”

Kentridge defined The Head & the Load as “not an opera, not a musical…it’s a drawing in performance, but it began with music.” For Philip Miller it was “a walking opera”, and he and Kentridge talked about a new art form being created. The other musician, Thuthuka Sibisi, spoke more about the importance of sound. He said that recordings had been made of approximately 60 African languages from the Africans who became prisoners of the Germans and were held in a camp outside Berlin. An attempt was even made to reproduce in the music score the sound quality of these recordings on wax cylinders.

The challenge for Philip Miller was “How do you ‘contemporise’ archive sounds, recreating and reimagining the archive…how didactic should the piece be?” Kentridge wanted to hold back from giving a lecture. He wanted to depict “history as a collage.” Also, “one needs to find an illogic” to express the madness of war. They were “making a piece about incomprehension” so the “madness of Dada” became one reference point.

This was “a kind of ethnographic drama,” and what it also incorporated was a division in the attitude of the Africans who took part in the war, a split between those who wanted to go, to become part of the Empire, and those who didn’t. This was incorporated in the choreography, and is expressed in the rendition of the national anthem, “God Save the King,” which gradually breaks down. A national anthem is about stripping people of their individuality, and the sense here is of people, who have their own queen, talking back to Europe. “They start claiming back a space, each singer coming in on a different tempo…coming back home on waves, on a wave-like movement” of song.

Kentridge skilfully uses a combination of clear and discordant sound with movement across the Turbine Hall to illustrate the profound ignorance and disrespect shown by the Europeans who tried to dominate pre-existing cultures which had their own language and traditions. One symbol of indigenous communication was the West African koro, a harp-like instrument that serves as a graphic reminder on stage of African culture that predated the European incursion and World War I. This imposing decorative instrument is made of a calabash cut in half covered with cow skin to make it resonant. It is a reminder that artful African music and instruments were ignored, misinterpreted or drowned out by the Europeans.

The enormous Turbine Hall adds another dimension of visible industrial structures to Kentridge’s complex fusion of film projection, dance, music, shadow play and the sounds of multiple European and African languages. The action takes place across a very long raised platform, with the audience confronted with diverse performances impossible to take in altogether. As Kentridge said, “You’re partly constructing which performance you’re seeing.” Sound overlaps or stands alone, a cacophony of competing, impossible to interpret sounds.

Live performers occupy the stage as lone players, as clusters of musicians inside movable enclosures, or on ladder-towers reflecting the hierarchy that enabled the large-scale recruitment of African porter/carriers. During the war, the English Committee for the Welfare of Africans was sufficiently aware of the native population to send them gramophones, banjos, harmonicas, and the ubiquitous hymn books. Familiar Kentridge elements such as megaphones are used to symbolise how the discordant sound is magnified, rendering meaning absurd.

The libretto is a collage of performers and projected images. It is made up of fragments of Frantz Fanon translated into siSwati, and Tristan Tzara into isiZulu. Wilfred Owen is translated into French and into what Kentridge refers to as “dog-barking.” Kentridge uses parts of Kurt Schwitter’s Ursonate, Setswana proverbs, Aime Cesaire, and phrases from a handbook of military drills. The industrial construction of the Turbine Hall is an appropriate container for this resonant and often discordant orchestration. The hall and the staging render more memorable a soulful African singer who communicates a quiet solo melody of regret and grief for the plight of over a million Africans.

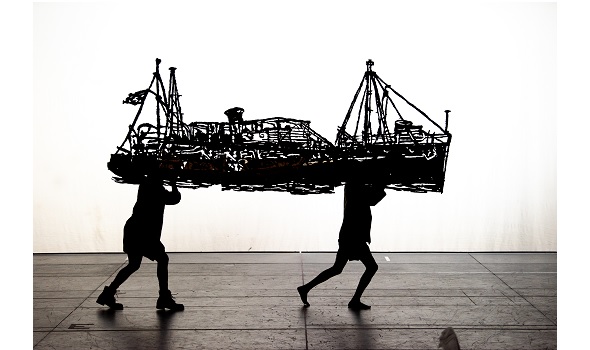

There is a persistent contrast between detail and shadow: the actors to the front of the stage whom we see in detail, plus large poignant projections of individuals to the rear. These detailed representations of individual actors and of enormous projections are part of Kentridge’s familiar use of shadows and silhouettes that obliterate detail into mass. Kentridge refers to Plato’s myth of the cave, and how what we take for reality may just be the shadows of objects passing in front of a fire.

The representations also remind the audience of the universality of these individual humans, and of how the endless supply of Africans could be reduced to repetitive movements, obscuring the individuals and indicating how the African was useful, indispensable, but nameless and infinitely replaceable. This commemoration of the forgotten porters/carriers is often projected on to lists of names on the rear screen, combined with the silhouettes of the carriers and their burdens.

The continual procession of carriers symbolises the vast number and anonymity of the Africans. The silhouettes projected on to the rear of the stage are enormous, thus enlarging the movement of these actors but obliterating their individual faces. Often on stage there are staccato sounds that might be weaponry, or breaking bones, marking the destruction of the carriers who worked without recognition and died without commemoration, discarded across the landscape that was once their home and was now occupied by strangers.

Kentridge spectacularly depicts how the wajungu, the white stranger, forced interminable burdens on the indigenous Africans who were regarded as replaceable. They perish without names, grave markers or commemoration. Through artwork that is familiar to international audiences (and which is currently on view at the Stephen Friedman Gallery, featuring Kentridge and other African artists), Kentridge fills the stage with processions of privileged European rulers, transported with the paraphernalia and heavy weapons of war from which the Africans will not gain and which will bring about their death in multitudes.

An exhausted porter is carried across the stage by another porter who cannot revive his burden, until the latter is bent into the shape of a cart. The African singer at the front of the stage sings a haunting melody while enlarged images are presented at the back showing Kentridge’s intricate paintings of birds. The mourning sound of the performer persists as these symbolic images of fragility are blasted apart one by one.

The relentless destruction of something intact and alive into an unidentifiable entity reflects the destruction of Africa itself, the breaking apart of borders by the Europeans who afterwards treated the continent as the spoils of war, dividing it between themselves. The once German colony of Tanganyika became part of British East Africa, with the French and Belgians also claiming their share of African land and dominance over the people.

The Head & the Load would reward more than a single viewing, in order to take in the multiple details, the complex interplay of graphic art, dance, animation and live music. At the press conference, Kentridge mentioned that there was a “utopian moment” some 50 years after the war when African leaders like Patrice Lumumba and Julius Nyerere came to the fore, and how we might now reflect – a further 50 years later – on what became of that utopian moment. Kentridge intended that The Head & the Load would help us to “recognise and record,” and we might now acknowledge and explore, and even alleviate, the contemporary parallels to these unrecognised burdens.

The Head & the Load will be shown at Park Avenue Armory in New York from 4-15 December 2018. More information can be found here