Editorial: Migrants are humans too

Editorial: Migrants are humans too

The situation at the Greece-Turkey border is the result of a shameful unwillingness to see migrants as human beings, to acknowledge their right to agency over their own lives, and to contemplate anything beyond short-term, sticking plaster approaches to the movement of human beings.

Many of the migrants gathered at the border have been used as pawns in a geopolitical game for years and are now once again being manipulated for political gains. While several EU countries have done good work resettling refugees in the last few years, we have seen a shameful lack of action more recently. In complete disregard of international law, Greece has now suspended the right to seek asylum, a despicable move that has been met shamefully with near silence by the EU.

We are calling for three things: all countries must immediately stop using migrants as pawns in their political games; Greece must immediately reinstate the right to seek asylum; and the EU must work towards a new bloc-wide resettlement scheme, one designed and implemented in dialogue with migrants and refugees themselves.

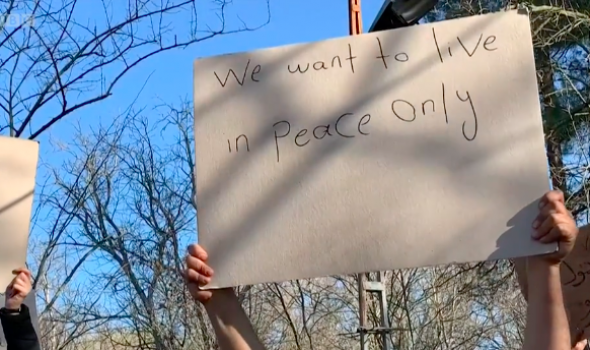

Those at the border with Greece don’t want the earth – in this BBC story, the migrants quoted talk about the need for an indoor toilet, a house, a safe future for their children. We all want these things and would resist or set out to seek them elsewhere if they were denied to us. Solving this crisis must begin with acknowledging that these are human beings who will move to seek safety and a better future for their children if they have to. After all, it could be any one of us.

Instead, what we’re seeing is the constant dehumanisation of these people, by politicians and the media. The word “people” is rarely used – instead they are rendered an abstract problem through words like “burden” and “pressure”, or an invasive threat through the description of Greece as Europe’s “shield”. Even discussions within the migration sector of the need to “decongest” the Greek islands risk disguising the individual humanity of the people living there with a dehumanising word that has connotations of sickness.

Descriptions of those at the border as “violent mobs” further strips these people of their humanity, as does the description of events there as “clashes”. This is not a meeting of equals – it’s a David and Goliath situation. While Greece has border guards, helicopters, thermal-vision vehicles, water cannon and tear gas, the people on the other side of the fence are unarmed, ordinary human beings in a desperate situation.

These people are being presented as a threat to Europe, to our way of life. But the only threat to that is currently from within: from commissioners and presidents and prime ministers who refuse to seek real solutions to this humanitarian crisis or to criticise border guards who fire rubber bullets at asylum seekers.

But perhaps this is understandable. The migrants at the border – and those living in squalor in the island camps – have been reduced in so many minds to an abstract threat, a burden to be borne, a problem to be managed. They are no longer human beings, making it easy to deny them basic human rights, to deny them agency over their own lives.

We are not calling for pity, or even for outrage. What we are calling for are rhetoric and policies that acknowledge these people – and all those who choose to move away from horror towards safety, from hopelessness towards hope – as human beings. Surely that’s not too much to ask.

TOP IMAGE: Screenshot from BBC video in this article