Living in Limbo: stories from the Brexit front line

Living in Limbo: stories from the Brexit front line

'Betrayal' is the prevalent emotional reaction of EU nationals living in the UK following the referendum, says Elena Remigi, founder and co-editor of a book that tells the stories of 144 Europeans and their experiences since the Brexit vote.

“There is a strong sense of betrayal among EU nationals,” says Remigi. “It’s natural to think that when you have rights you live your life based on a certain premise, and suddenly somebody tells you ‘Your rights are not guaranteed, and you would be good bargaining capital.’ You’re reduced to a thing…”

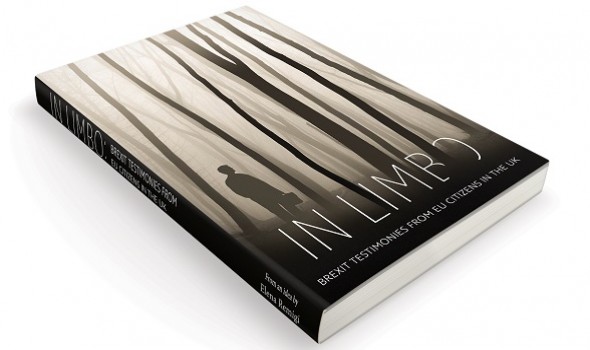

The book, 'In Limbo', which she co-edited with Véronique Martin and Tim Sykes, dedicates a chapter to each of the top five emotional reactions - sorrow, disappointment, worry, anger and betrayal - found in the research carried out for the book by Dr Helen De Cruz, a philosophy lecturer at Oxford Brookes University.

Her idea for the book came when she noticed people where sharing their stories on Facebook. She thought that compiling the voices of those who were not consulted during the referendum on 24 June 2016 would give them a better chance of being heard as a strong united voice.

Since the Brexit vote, she says, it’s a question not only of citizenship but also of the psychological limbo of living without certainty. When people who have made their homes in the UK are made to feel unwanted, they begin questioning where home is.

Before Brexit, Remigi says, “we felt adopted by this country, we felt part of the family. Suddenly we’re told we’re no longer welcome. This is a very hard thing to accept psychologically.”

Italian-born Remigi first visited the UK in 1984 and subsequently moved to Ireland in 1999 because of her husband's work. Six years later they settled in Berkshire in south-east England with their son, who is now studying at Oxford University. She says, “I Always felt the United Kingdom was a very tolerant multicultural, open place and I wanted to live in a place that embraced all cultures and had that flare.”

But the spike in hate crimes has made Remigi question whether the British have truly accepted incomers. Some people appear to think that recent events have validated racial abuse and making EU nationals feel unwelcome.

“This allows people who do not want immigrants here to ask, ‘When are they sending you home?’ That’s a question that many of us in the UK get asked. It can be worse for EU nationals living in small towns,” she says.

“There have been attacks. I feel sorry for the Polish community and many Eastern Europeans because they are the ones paying the highest price. Us as well. My son was shouted at on the train when speaking Italian on the phone to his dad.”

Remigi hopes the human stories in the book touch people’s hearts and encourage reflection on the type of country they want for themselves and their children. Her aim is to raise awareness among politicians and change public perceptions.

She has sent over 750 books to politicians in Britain and across Europe: “We found a staggering level of ignorance among politicians. They have no idea what ‘permanent residency’ means, what the many issues relating to dual nationality are, and so on. Sometimes they don’t understand the suffering.

“It was important that we sent the book to politicians on both sides of the channel, to Brussels, to ambassadors from every EU country in the UK, to political influencers, in the hope that by reading the book they would start understanding more of the problem”

She is optimistic that change will happen by sharing stories like that told by Elly, a 76-year-old Dutch widow who has lived in the UK for 53 years. Elly’s marriage is considered dissolved because her husband is dead and she cannot obtain permanent residency because she cannot prove she had worked in the UK for more than five years.

Says Remigi, “Imagine an elderly person who has lived here all her life – her only son lives in the UK – she has no family back in Holland. It’s terrifying. I always think of Elly and I ask myself ‘Is it right for a person of that age to have to worry so much and live in constant fear that something may happen to her?'”

There are worse stories, she says. Some people are homeless or have mental health problems and live in terrible situations but don’t want to give their testimonies for fear of being recognised (“There is a much darker side to this”).

Remigi admits her own personal experience has not been as bad as the many stories she has heard and recalls an incident that motivated completion of the book.

“After getting residency I went for my citizenship. I am a dependant spouse and I was told I had to prove that I had lived in the UK for five years. I took all my documents to the National Checking Service. My documents proved I own a house, I own a car, I pay my bills, I’ve done all my tests, I have my doctors here. These were deemed insufficient. What more could I prove? I had to take another five kilos of documents to the Home Office with letters from my priest, my friends and others. When leaving, I saw a German lady in tears – because, like me, she was asked to prove this and that – and I felt this is not right.”

The 49-year-old says her life has been completely taken over by the book. When she’s not sending the book to politicians or giving interviews, she is speaking at marches and other engagements: “This is my way of fighting and letting the world know there is a problem. It’s very important to speak out and not be afraid.

“I speak to people in other countries about what is happening and they cannot believe it. They say, ‘That can’t be true.’ It’s even difficult for us in the UK to understand what is happening.”

She urges people to remember their role in society and remain alert to what is going on, “rather than thinking it will be fine, because that’s not good enough. And once you realise it’s not fine -find ways of being active in the debate: go to rallies, go to marches, read about what is happening and do something to change it. People have different ways of speaking out and you need to find your own.”

Remigi thinks many EU nationals are afraid their rights will be reduced to the rights of non-EU nationals. They have become aware of the way migrants from outside the EU have been treated within the immigration system for many years.

“I think it has created a much deeper understanding, certainly in me it has. Lately I have read much more about the way non-EU nationals are treated. I read about deportations. I read more about topics I wasn’t aware of. You understand more when you go through the same things or when you see others who are very close to you go through these things.”

She believes that’s the good side of a sad and difficult situation: it has created a closer bond among EU nationals and better understanding towards immigrants in general.

Helpful links and information:

Contact: [email protected]

Facebook: www.facebook.com/OurBrexitTestimonies

Twitter: @InLimboBrexit

Blog: http://www.ourbrexitblog.eu/