Lenny Henry’s home truths

Lenny Henry’s home truths

The third in an occasional series about TV and radio programmes about migrants and migration in Britain.

In Lenny Henry: Commonwealth Kid the British comedian says “The Commonwealth made me who I am”. That’s a bit far-fetched, I thought – and then realised that it was because of the existence of the post-colonial “club” of nations that some of his family were able to emigrate from Jamaica to Britain.

Most of the hour-long BBC1 programme is taken up with his trip to Jamaica, in which he veers between good-natured banter and moving emotion. He also lobs some gentle questions about the Commonwealth to passers-by and gets predictably vague reactions.

It’s mostly smilingly amiable, more like the BBC1 genealogy show Who do you think you are? than a probing geopolitical inquiry, and he even manages to pick his way through slavery (throwing in the, literally, killer fact, that on arrival the average life expectancy of a slave was nine years). On migration, however, Henry gets up close and personal.

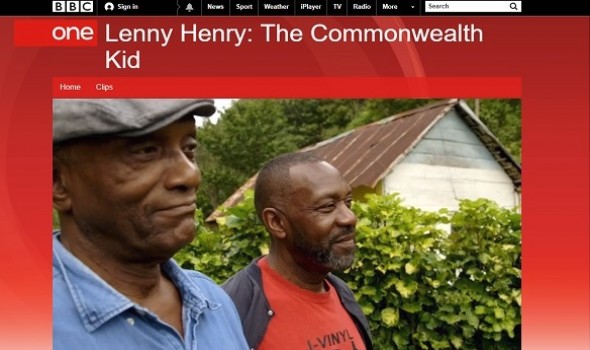

His conversations with his brother, who joined their mother in Britain but returned to Jamaica, are genuinely moving, particularly when discussing their divergent paths through life and even more so when they visit their mother’s former home, with its tiny overgrown graves holding the remains of their dead siblings: “I see now why she had to go, if this was it … In a way, she made a decision to leave this to go to Britain and to find an alternative way of being, because this way wasn’t working.”

Henry could hardly be more successful: he’s a radio and TV star and actor, a household name and a knight: we see the sword tap on his shoulder though as a loyal subject he doesn’t disclose what the Queen said. Musing on what would have become of him had he stayed in Jamaica, he points to the “many advantages to growing up in UK”. He even coaxes his brother, apparently happy with his decision to return to Jamaica, into admitting he has a British rather than a Jamaican passport because of the travel advantages it confers. Yet with all these benefits of migration – fame, prestige, money, status, travel, opportunities – Henry says, “I do feel like a Brit. But I feel Jamaican as well. I’ve never been sure where home is.”

This is one of the dividing lines in attitudes to migration: the shift in thinking held by an older generation, who see borders as clear lines (the Tebbit test: which cricket team do you support? England or India/Pakistan/Bangladesh) to a more complex, permeable, shape-shifting approach, which understands that loyalties and attachments sometimes lie with the old country and sometimes lie with the adopted country.

“It’s a harsh life,” say the brothers, musing over the children’s tombs.

“This is roots.”

“Proper roots, isn’t it?”

It’s perfectly reasonable to cherish both standpoints, to shiver at the downsides and yet to feel attached to them.

The programme also lightly pinpoints a feeling common to many migrants returning for a home visit: “I’m, a foreigner when I come here.”

And, praise be, the programme even touches on migration's little secret: the many British migrants abroad, in this case the Caribbean, who strive for special status by describing themselves as expats.

Overall, Henry’s down-to-earth, non-judgemental, undoctrainaire approach must have helped some white Britons’ understanding of the position of the Windrush generation (as well as perhaps the understanding of a rarely reported section of the UK community - racist migrants).

On the Commonwealth, the 53-nation grouping of mainly ex-British colonies, the programme has less to say. Henry says his mother’s escape from a hard life, before Britain closed the door to Commonwealth migrants, turned him into a Commonwealth Boy. But really he was a Jamaican boy who came here under a comparatively open border policy (and let’s not forget that Caribbean migrants were invited here, as government policy, to fill vacancies). The word Commonwealth was bandied about but it meant little. Britain essentially turned its back on the Commonwealth, though now a few Brexiteers have rediscovered its potential as a trading friend, minus the open borders.

Henry concludes by saying that “In the end, the Commonwealth, good or bad, is about all of us being one thing, universal, and we’re gonna keep changing until we get it right. We may never get it right but we’re not gonna stop trying.”

But that’s meaningless blather compared with the home truths that preceded it.

• Lenny Henry’s Commonwealth Kid

+ 'My millionaire migrant boss' and the unemployed Brits who tried working in his hotel

+ Collateral: TV crime drama takes on migration