Congo: bringing history to life

Congo: bringing history to life

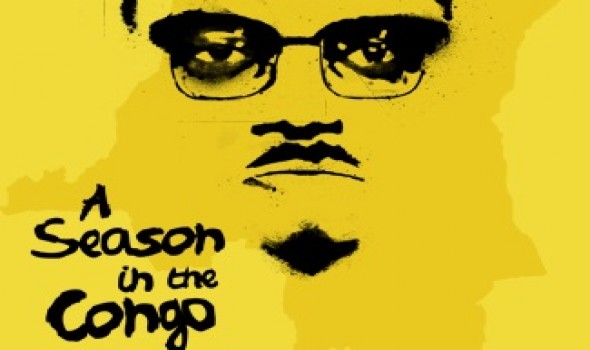

“The least we can do is know what happened,” says Joe Wright, director of 'A Season in the Congo' at the Young Vic in London. I agree: that alone is reason enough to stage a neglected play about a forgotten episode in history. A Season in the Congo Few people born after the year of Congolese Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba’s assassination in 1961 know about the scarcely credible murderousness, greed and sadism of Belgian colonial rule and the country’s total lack of preparation for independence, and few now are aware of the cataclysmic Cold War events covered by the play, events that five years later spawned the 32-year kleptocracy of General Mobutu, darling of the West. Later still came years of killing and pillage in what has been called “Africa’s first world war”, as surrounding and distant countries were sucked in or took advantage of instability to plunder Congo’s resources. Even today the rape, conflict and exploitation continue. Congo, which temporarily became Zaire under Mobutu, is an embodiment of the resource curse. “Conflict coltan” from Congo probably helps makes your mobile phone work: the beginning of coltan as an important mineral, crucial to technological products “occurred as warlords and armies in the eastern Congo converted artisanal mining operations … into slave labour regimes to earn hard currency to finance their militias”, in the words of a study by a social anthropologist. So we in the West (and others) cannot look the other way and pretend not to notice. That’s also true in the specific case of Lumumba’s murder. Only a few weeks ago, as reported by Oneworld, a member of the British House of Lords, David Lea, recalled a conversation over a cup of tea with the late Daphne Park, the British consul and first secretary (and thus, he said, the local head of MI6, Britain’s secret intelligence service) in what is now Kinshasa: “I mentioned the uproar surrounding Lumumba’s abduction and murder, and recalled the theory that M16 might have something to do with it. ‘We did,’ she replied. ‘I organised it.’” There’s another contemporary echo from Lumumba’s death. Soon after the events shown on stage, UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjold was killed in a mysterious plane crash. A recent letter in the London Review of Books suggested that Park may have helped engineer Hammarskjold’s death. He claimed that documents from South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission had implicated the CIA and British intelligence in a plot to remove the Swedish Secretary-General because they believed he stood against the secession of Congo’s Katanga’s region – rich in minerals and a buffer against possible communist incursion (as the play recounts). An independent inquiry into Hammarskjold’s death, headed by a British judge, will deliver its findings in a few weeks. We’ll have to wait for that: meanwhile, it’s interesting to see such an unflattering portray of Hammarskjold and the UN in A Season in the Congo ("The UN is a tale told oto frightren children.") Aimé Césaire, the polymath from Martinique – who is virtually unknown in Britain – wrote this “decolonisation drama” in 1966 when independence and the ensuing struggle for power and resources were still fresh in the mind. More details have emerged since then (Lumumba was probably killed by Belgians rather than Congolese), and perspectives change with time, but the events were played out in public and it was clear contemporaneously what was going on. Césaire’s play rips through the key incidents in the story, so the emphasis is on the drama of events rather than the drama of personalities. It’s like a Reduced Shakespeare Company version of Congolese history. We learn nothing of the emotional and personal drives and interactions between the main political characters – leading one critic to say that this was the play’s first performance in UK and he hoped the last: “I come to bury Césaire, not to praise him.” That’s an amusing line, but misses the drive, ebullience, colour, staging, music, inventiveness, humour, symbolism of the production. It might be a history lesson, but it’s the history lesson we all dreamed of at school. You know it’s going to be fun when you see the front rows have been turned into nightclub tables. There are giant, grotesque talking puppets; tiny parachutes falling on the audience to illustrate the arrival of Belgian paratroopers; dance that turns into death throes; a Belgian king whose train unrolls regally from the balcony to the ground. Brilliant. And the acting is excellent, from Chiwetel Ejiofor as the beer-salesman-turned-prime minister who relies on electoral legitimacy that turns out to be no more than a puff of air when confronted by military and economic power, to musician Kabongo Tshisensa, a griot scene-stealer who occasionally moves to the front of the stage to deliver his short summaries. So even though it’s not a great play, it’s important. Praise to Césaire for tackling such a complex and important subject, and praise to the team that has breathed life and vitality into it. Daniel Nelson is Editor of OneWorld's London Events page: http://www.oneworld.org/events * A Season in the Congo is at the Young Vic, The Cut, Waterloo, SE1, until 24 August. Info: 7922 2922. Image by Young Vic